Joined Feb 2023

276 Posts | 416+

Colorado

The 1960s Divorce Revolution in America

For most of United States’ history, divorce was a rare occurrence and an insignificant feature of family and social relationships. In the first sixty years of the twentieth century, divorce became more common, but it was hardly commonplace. After 1960, the rate of divorce in the US accelerated at a dazzling pace. It doubled in roughly a decade and continued its upward climb until the early 1980s, when it stabilized at the highest level among advanced Western societies.

Prior to 1960, divorce was generally considered to be against the public interest, and civil courts refused to grant a divorce except if one party to the marriage had betrayed the "innocent spouse." Thus, a spouse suing for divorce in most states had to show a "fault" such as abandonment, cruelty, incurable mental illness, or adultery. If an "innocent" husband and wife wished to separate, or if both were guilty, neither spouse would be allowed to escape the bonds of marriage.

By the mid- to late 19th century, divorce rates in the United States were growing steadily, and Americans obtained more divorces annually than were granted in all of Europe. The popular acceptance of divorce as an alternative to marital unhappiness, decay of the belief in immortality and future punishment, discontent with the existing constitution of society, the habits of mobility created by better transportation, and the greater independence of women resulting in their enlarged legal rights and greater opportunities of self-support, as well as the reduction in cost of obtaining a divorce all contributed to the growing trend. The divorce rate grew from 3 couples per thousand in 1890, to 8 couples per thousand by 1920.

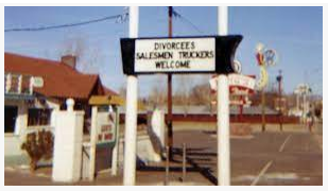

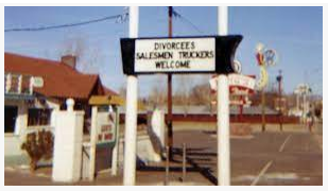

The rate of divorce continued its upward trend through the 1940s and 1950s, spiking at the end of the Second World War, when both the rate of marriage and rate of divorce coincided to reach a high point. The increased divorce rate was somewhat aided by reductions in residency requirements in some states such as Nevada, Idaho and Arkansas; and internationally in Mexico and France that promoted connections to their hospitality industries.

Beginning in the late 1950s, Americans began to change their ideas about the individual's obligations to family and society and how these ideas have shaped a culture of divorce. The making of a divorce culture can be described as a change away from an ethic of obligation to others and a more acute consciousness of their responsibility to attend to their own individual needs and interests. This new thinking suggested that there was the moral obligation to look after oneself that was at least as important as the moral obligation to look after others.

Marriage and Divorce Rates in the US Since 1870

During the 1960s, the American Bar Association created a Family Law section in many state courts, and pushed strongly for no-fault divorce legislation. In 1969, California became the first state to pass a no-fault divorce law. The introduction of no-fault divorce that allowed unilateral action and lent moral legitimacy to the process, opened the floodgates in the 1970s leading to a dramatic rise in divorce rates in the United States.

Multiple changes in American social structure coincided in the 1960s and 1970s to contribute to the divorce revolution. Spouses found it easier to find extramarital partners, and came to have higher, and often unrealistic, expectations of their marital relationships. Increases in women's employment coupled with new career opportunities did their part to drive up the divorce rate, as wives felt freer in the late 1960s and 1970s to leave marriages that were abusive or that they found unsatisfying.

Many mainline Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish leaders were caught up in the spirit of the cultural changes, and lent explicit or implicit support to the divorce revolution sweeping across American society. The 1970s marked the period when, for many Americans, a more institutional model of marriage was shattered. In the older, institutional model of marriage, parents were supposed to stick together for their sake. The view was that divorce could leave an indelible emotional scar on children, and would also harm their social and economic future. In 1962 about half of American women agreed with the idea that "when there are children in the family parents should stay together even if they don't get along." By 1977, only 20% of American women held this view.

All states now allow no-fault divorce on grounds such as irreconcilable differences, irremediable breakdown, and loss of affection; and all states recognize divorces granted by any other state, along with the imposition of a minimum time of residence to file for a divorce. Nevada and Idaho currently being the shortest at six weeks. Some states mandate a separation period before no-fault divorce. Mississippi, South Dakota and Tennessee are the only states that require mutual consent for no-fault divorce. The rest of the states permit unilateral no-fault divorce.

The Great Disruption by Francis Fukuyama. Free Press publishers, 2000.

The Divorce Revolution: The Unexpected Social and Economic Consequences for Women and Children in America by Lenore Weitzman. Free Press publishers, 1985.

“Escape from the Gilded Cage”, by April White. Smithsonian Magazine, June 2022.

For most of United States’ history, divorce was a rare occurrence and an insignificant feature of family and social relationships. In the first sixty years of the twentieth century, divorce became more common, but it was hardly commonplace. After 1960, the rate of divorce in the US accelerated at a dazzling pace. It doubled in roughly a decade and continued its upward climb until the early 1980s, when it stabilized at the highest level among advanced Western societies.

Prior to 1960, divorce was generally considered to be against the public interest, and civil courts refused to grant a divorce except if one party to the marriage had betrayed the "innocent spouse." Thus, a spouse suing for divorce in most states had to show a "fault" such as abandonment, cruelty, incurable mental illness, or adultery. If an "innocent" husband and wife wished to separate, or if both were guilty, neither spouse would be allowed to escape the bonds of marriage.

By the mid- to late 19th century, divorce rates in the United States were growing steadily, and Americans obtained more divorces annually than were granted in all of Europe. The popular acceptance of divorce as an alternative to marital unhappiness, decay of the belief in immortality and future punishment, discontent with the existing constitution of society, the habits of mobility created by better transportation, and the greater independence of women resulting in their enlarged legal rights and greater opportunities of self-support, as well as the reduction in cost of obtaining a divorce all contributed to the growing trend. The divorce rate grew from 3 couples per thousand in 1890, to 8 couples per thousand by 1920.

The rate of divorce continued its upward trend through the 1940s and 1950s, spiking at the end of the Second World War, when both the rate of marriage and rate of divorce coincided to reach a high point. The increased divorce rate was somewhat aided by reductions in residency requirements in some states such as Nevada, Idaho and Arkansas; and internationally in Mexico and France that promoted connections to their hospitality industries.

Beginning in the late 1950s, Americans began to change their ideas about the individual's obligations to family and society and how these ideas have shaped a culture of divorce. The making of a divorce culture can be described as a change away from an ethic of obligation to others and a more acute consciousness of their responsibility to attend to their own individual needs and interests. This new thinking suggested that there was the moral obligation to look after oneself that was at least as important as the moral obligation to look after others.

Marriage and Divorce Rates in the US Since 1870

During the 1960s, the American Bar Association created a Family Law section in many state courts, and pushed strongly for no-fault divorce legislation. In 1969, California became the first state to pass a no-fault divorce law. The introduction of no-fault divorce that allowed unilateral action and lent moral legitimacy to the process, opened the floodgates in the 1970s leading to a dramatic rise in divorce rates in the United States.

Multiple changes in American social structure coincided in the 1960s and 1970s to contribute to the divorce revolution. Spouses found it easier to find extramarital partners, and came to have higher, and often unrealistic, expectations of their marital relationships. Increases in women's employment coupled with new career opportunities did their part to drive up the divorce rate, as wives felt freer in the late 1960s and 1970s to leave marriages that were abusive or that they found unsatisfying.

Many mainline Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish leaders were caught up in the spirit of the cultural changes, and lent explicit or implicit support to the divorce revolution sweeping across American society. The 1970s marked the period when, for many Americans, a more institutional model of marriage was shattered. In the older, institutional model of marriage, parents were supposed to stick together for their sake. The view was that divorce could leave an indelible emotional scar on children, and would also harm their social and economic future. In 1962 about half of American women agreed with the idea that "when there are children in the family parents should stay together even if they don't get along." By 1977, only 20% of American women held this view.

All states now allow no-fault divorce on grounds such as irreconcilable differences, irremediable breakdown, and loss of affection; and all states recognize divorces granted by any other state, along with the imposition of a minimum time of residence to file for a divorce. Nevada and Idaho currently being the shortest at six weeks. Some states mandate a separation period before no-fault divorce. Mississippi, South Dakota and Tennessee are the only states that require mutual consent for no-fault divorce. The rest of the states permit unilateral no-fault divorce.

The Great Disruption by Francis Fukuyama. Free Press publishers, 2000.

The Divorce Revolution: The Unexpected Social and Economic Consequences for Women and Children in America by Lenore Weitzman. Free Press publishers, 1985.

“Escape from the Gilded Cage”, by April White. Smithsonian Magazine, June 2022.